Perhaps the greatest thing about being asked to give talks and workshops is we get to see the practical application of Skimming Stones; we have the pleasure of spending time among people who may be like-minded but perhaps haven’t fully embraced the idea of getting out there and trying the activities in our book. Yesterday, at Cock and Bull Festival was one such experience.

After a long drive from Yorkshire to the countryside around Bath, I followed signs to the farm that played host to this lovely festival. For anyone that doesn’t know it. Cock and Bull is put on to raise money for charity ‘Jamie’s Farm‘, which takes kids from the inner city and gives them a taste of rural life on a farm for a few weeks. it is worthy and profoundly affecting for all involved, as this video shows.

Travelling through the demarked windy lanes (stenciled bulls and cockerels tacked to boards among banks of meadowsweet) I eventually arrived during the Graveyard Shift of any self-respecting festival: Sunday late morning. Bleary-eyed revellers staggered from tents and trance still boomed from barns for those refusing to give up their Saturday evening. A bearded man in a dress, an obligatory sight at many festivals, still clung to his vast jar of cider like it was a baby.

Mercifully, after most people started to shake away sleep with strong coffees, the talk commenced in the cool shade of a stone barn. The bales of hay/seats soon filled with people until it was standing room only. The talk seemed to go down very well with plenty of crowd participation and half an hour of questions and answers before a book signing. Then it was time to put my money where my mouth had been rabbiting for the last hour.

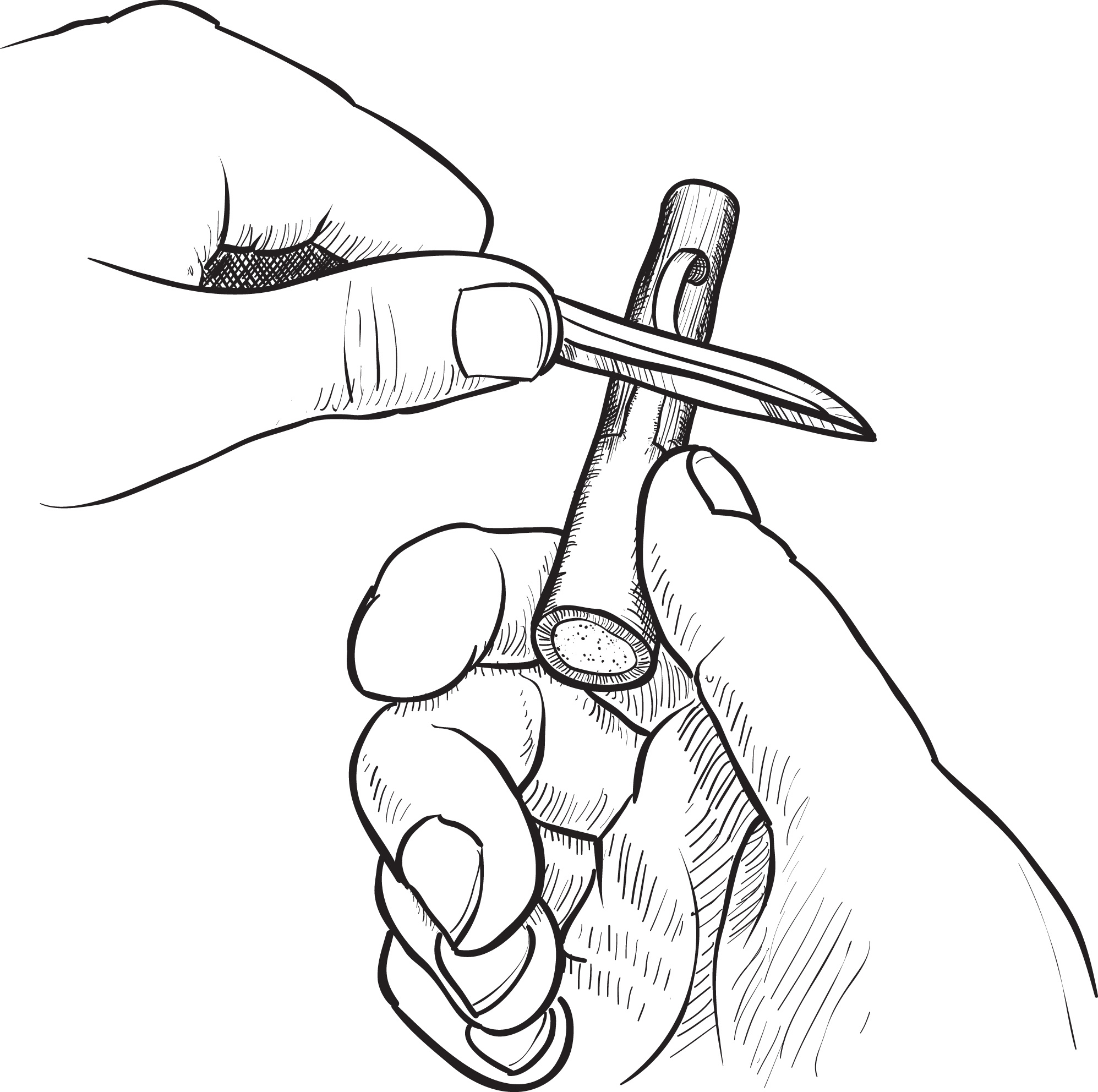

I was volunteered to lead a forage around the farms hedgerows with anyone that might be interested. Twenty five or so people were. A multi-cultural lot, I counted Bulgarians, Italians and even Scots among our numbers. Thankfully, our summer hedgerows rarely disappoint for wild food and I was soon pointing out and chomping on some old favourites (nettles, burdock, meadowsweet, dandelions) as well as some lesser known greens (chickweed, vetch, cow parsley). In a field off the track, chamomile grew in waves, interspersed by pineapple weed, dock and rat’s tail plantain. In the boundary hedges, sloes had formed early, as well as hawthorn and green blackberries. Finally we came upon some Jack-by-the-hedge – currently enjoying its second wind of the year and a subtle, garlic flavoured leaf and member of the mustard family.

The group followed with cameras, notepads and cries of ‘that’s REALLY bitter’ (dandelion – it needs storing in water for a few days or forcing by covering when young) and ‘absolutely lovely’ (Jack-by-the-hedge, vetch and chickweed). All said they couldn’t believe the variety and range of youtube 2 mp3 online converter things to eat or brew up only a few metres from the gate. As we write in the book, foraging focuses us; it stops us from just pacing over a field or past a hedge and gives us a new way of looking and interacting with the landscape.

After a good walk in the sunshine, I wanted to offer refreshments and had fortunately made a jar of Cowen’s Famous Hedgerow Pesto the previous night for the drive down. I had eaten the bagels I was going to dip into it before even leaving Yorkshire, leaving a jar of cracking stuff for my new students.

Cowen’s Famous Hedgerow Pesto recipe

This recipe is so easy and provides a delicious, citrusy, garlicky alternative to the Italian stuff. Gather two good handfuls of Jack-by-the-hedge leaves, a bunch of sorrel (wood or field), some nettle leaves and blend with toasted walnuts or hazel cobs. Add olive oil or Yorkshire rapeseed and salt and pepper to get that pesto consistency and you are done. You can add parmesan too (or Wensleydale if you are in Yorkshire) and then blend again. Serve over fresh pasta with vetch flowers on top, as a dip for bread, or as a side for roast chicken.

This recipe is so easy and provides a delicious, citrusy, garlicky alternative to the Italian stuff. Gather two good handfuls of Jack-by-the-hedge leaves, a bunch of sorrel (wood or field), some nettle leaves and blend with toasted walnuts or hazel cobs. Add olive oil or Yorkshire rapeseed and salt and pepper to get that pesto consistency and you are done. You can add parmesan too (or Wensleydale if you are in Yorkshire) and then blend again. Serve over fresh pasta with vetch flowers on top, as a dip for bread, or as a side for roast chicken.

To feed the hungry foragers, I opened the jar and sliced a lovely white bloomer donated by the friendly bakers at the festival. Before I could even get my camera out, the jar and the plate had been wolfed down. Still, it was great that everyone enjoyed it so much!

To say he walks the road less travelled is somewhat of an understatement. His latest book Scarp traces a path over the fourteen-mile ridge of land on the fringes of Northern London, through time, in and out of consciousness and between fantasy and truths that are stranger than fiction.

To say he walks the road less travelled is somewhat of an understatement. His latest book Scarp traces a path over the fourteen-mile ridge of land on the fringes of Northern London, through time, in and out of consciousness and between fantasy and truths that are stranger than fiction.